Kenya schools reflect Kenya's digital divide, with some embracing AI while others rely on traditional methods. (Photo© Daisy Okiring)

By Daisy Okiring

Nairobi Kenya, 5th August, 2025

What if a nation’s digital future is being built on a foundation of unequal access? In Kenya, the promise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is poised to transform education, but it is arriving on two different timetables. This stark reality is forging a great fault line in the nation’s educational landscape, threatening to deepen existing inequalities.

While one student in Nairobi might use a sleek smartphone to interact with an AI-powered tutor, a child in a remote village might have never heard of the technology. This creates a paradox: a country with a rapidly growing tech sector and ambitious national digital strategies, yet with millions of citizens still on the wrong side of the digital divide.

The question is not if AI will change Kenyan education, but rather, who will be part of the change, and who will be left behind? This article explores how Kenya is navigating this complex challenge, examining the social, economic, and ethical dimensions of integrating AI into its education system and the urgent need to ensure this revolution is inclusive for all.

The digital chasm creates a tale of two Kenyas

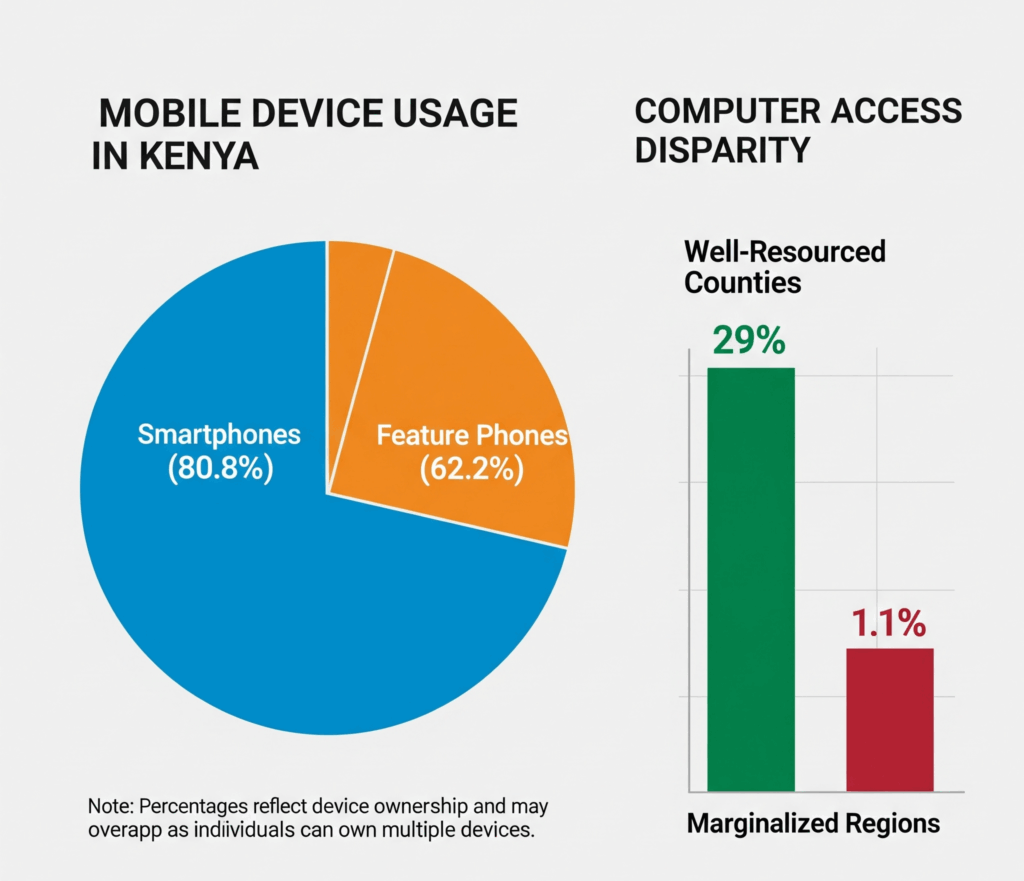

The numbers tell a story of immense progress but also of deep disparity. According to the latest data from the Communications Authority of Kenya (CA), mobile data subscriptions have soared to 57.18 million, a testament to the nation’s rapid connectivity. However, this impressive figure masks a critical truth: while smartphone adoption is on the rise with 42.35 million devices and an impressive penetration rate of 80.8%, an astonishing 32.5 million Kenyans still rely on basic feature phones. This is a crucial distinction, as a feature phone, while offering basic communication, cannot access the rich, interactive learning platforms that define modern AI-driven education.

This chasm is both geographic and economic. Internet penetration stands at around 48% nationally, yet computer access in well-resourced counties is nearly 29%, a figure that plummets to a mere 1.1% in marginalized regions like Mandera and Marsabit. In these areas, the lack of reliable electricity, the high cost of data, and the absence of a robust digital infrastructure mean that concepts like e-learning and AI-powered tools are a distant dream.

Also Read: A nation eating itself: How Kenya’s poor are being left to die hungry

For a child in Turkana, the focus remains on having a textbook to read, not a virtual assistant to guide them. The divide is not just about technology; it’s about opportunity, and it risks creating a generational gap in skills and knowledge that will be difficult to close.

This divide is the central challenge that Kenya’s ambitious National AI Strategy for 2025-2030 must overcome. The strategy is built on a vision of leveraging local data and talent, but its success will be measured by its ability to reach far beyond the high-speed fibre networks of the major cities. It must address the last-mile challenge, ensuring that every citizen, regardless of their location or socioeconomic status, can participate in the digital revolution.

AI emerges as a co-pilot in the overwhelmed classroom

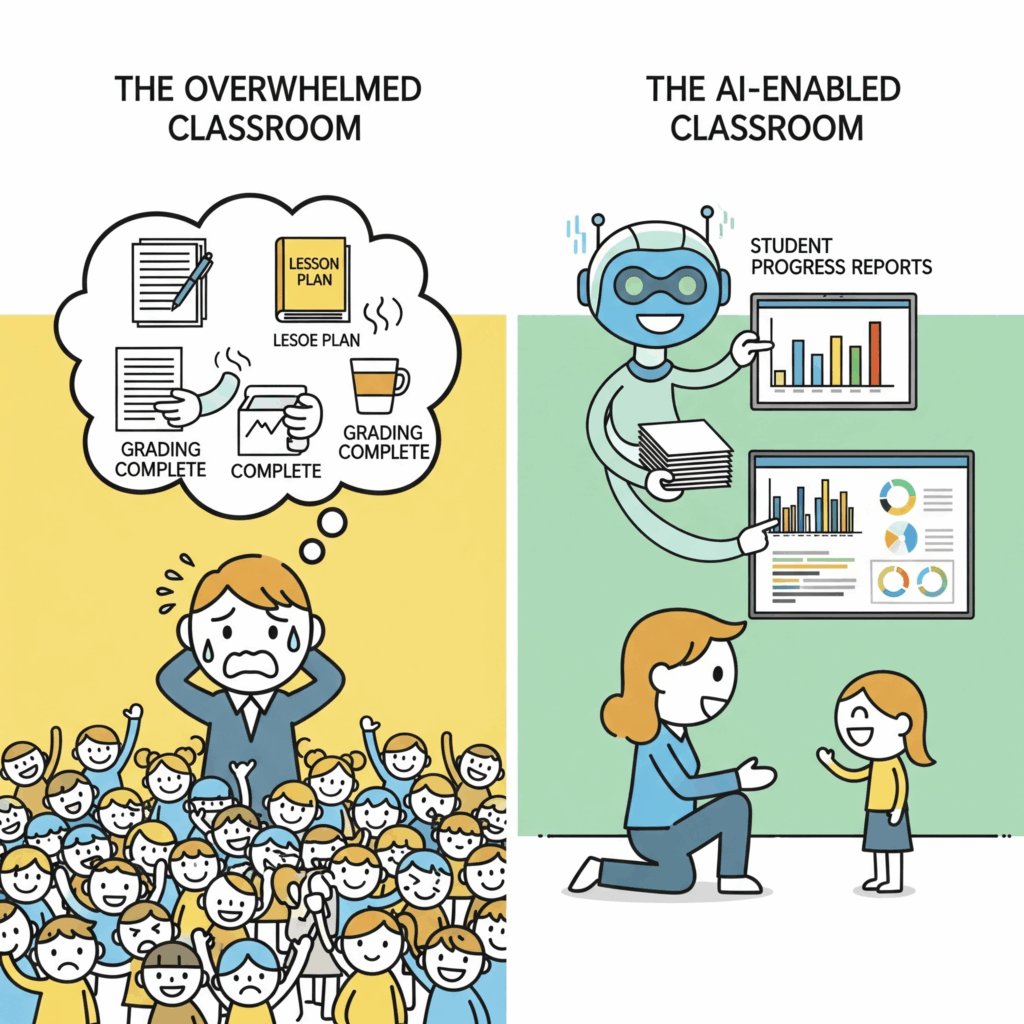

Kenya’s education system is a marvel of human resilience and ambition, yet it is stretched to its limits. The Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC) is a visionary policy designed to nurture critical thinking and practical skills, moving away from a rigid, exam-focused system. However, its implementation has been hobbled by systemic strain, particularly the crushing student-to-teacher ratios in many public schools. In a country where the average primary student-to-teacher ratio can reach 40:1, and in some rural areas soar to a staggering 70:1, personalized learning is a near-impossibility.

Teachers are buried under a mountain of administrative tasks—lesson planning, grading, and tracking progress—leaving little time for the kind of individualized mentorship that the CBC demands. In this environment, a student who is struggling often falls through the cracks, with teachers simply lacking the capacity to provide targeted support.

This is where AI is emerging not as a replacement for human educators, but as a powerful co-pilot. As Professor Maurice Oduor Okoth, a leading voice on AI in education, puts it, AI offers “a scalable solution to bridge this gap by supplementing the role of teachers with intelligent systems that offer real-time feedback and personalized learning experiences.”

Kenyan EdTech innovators are pioneering homegrown solutions to this crisis. Platforms like M-Shule use AI to continuously analyze a student’s performance via low-tech channels like SMS, generating personalized learning tracks to build their skills. This approach is powerful because it works on basic feature phones, making it accessible to a far greater number of students than a web-based app. The platforms offer tailored practice problems and instant feedback, helping students master concepts at their own pace.

Also Read: The hidden plague of microplastics in Kenya’s food chain

For teachers, these platforms automate assessment and generate real-time performance reports, freeing them from the drudgery of administrative work to focus on what matters most: mentoring and inspiring. By offloading repetitive tasks, AI allows educators to reclaim their time and energy, turning them into facilitators of learning rather than simply transmitters of information.

AI breaks down language barriers and goes beyond textbooks

The power of AI goes beyond just personalized learning; it is helping to dismantle the long-standing barriers of language and access. A project at Maseno University, for example, has developed an AI-enabled tool that translates between English and Kenyan sign language, providing a lifeline for deaf students who were previously marginalized from mainstream education. This single innovation is a profound act of educational equity, allowing students to engage with their peers and instructors in a more meaningful way.

These tools ensure that the rich linguistic and cultural diversity of Kenya is not a weakness to be overcome, but a strength to be leveraged in the classroom. However, this is not without its challenges. The article “Global Indigenous: Fears of AI causing cultural erasure in Africa” points out that while AI tools can be multilingual, they are often monocultural, and their training data rarely includes indigenous languages or ways of knowing. This highlights a critical ethical concern—that without careful, localized development, AI could inadvertently contribute to the erosion of cultural identity.

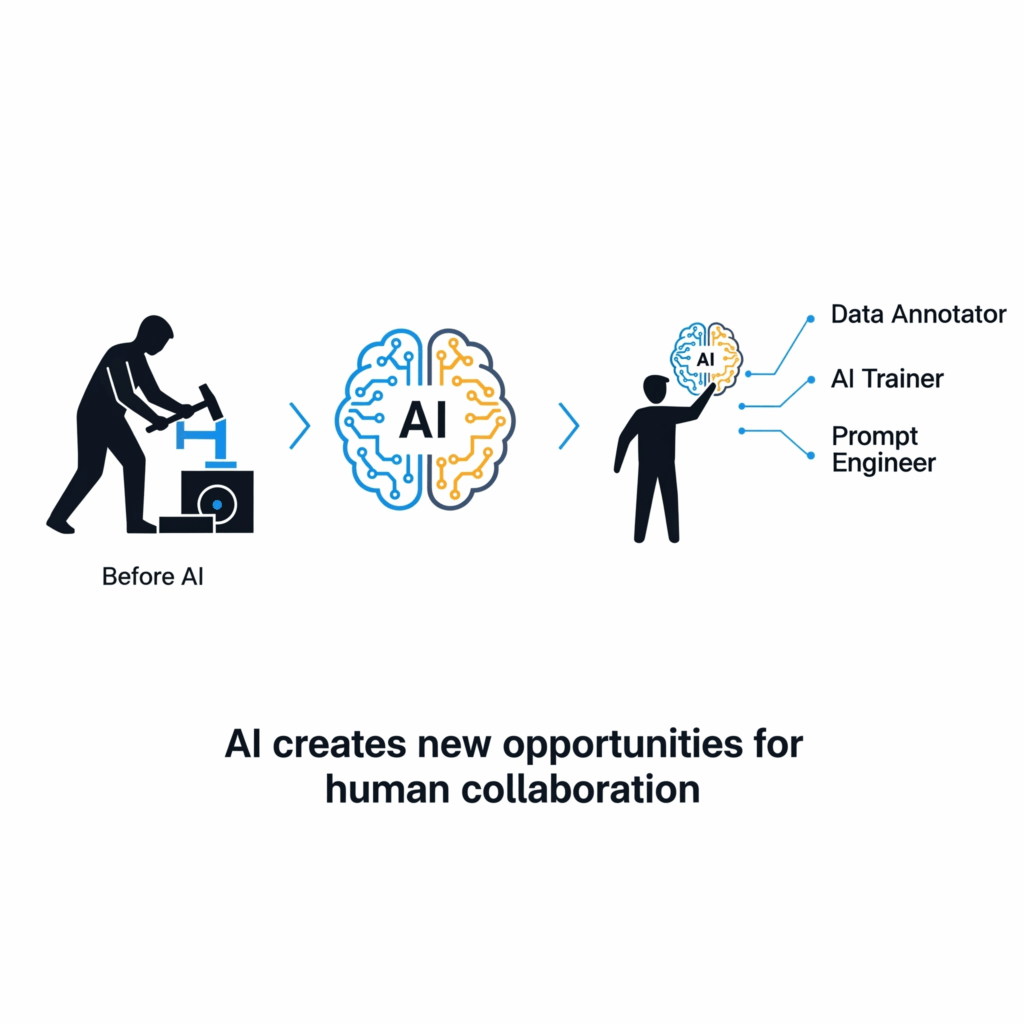

The human element is reshaping Kenya’s workforce

At the heart of this transformation are the people. Local innovators and entrepreneurs are at the forefront of the movement, building companies that solve specific educational problems with a deep understanding of the local context. Festus Kiragu, a director at Cloudfactory Kenya, a firm that has evolved from simple data transcription to complex AI-powered tasks, emphasizes the human element at the core of this technological shift.

“We still need people to tell machines what to do and verify what they produce,” Kiragu notes. “And that is creating jobs—lots of jobs.” This sentiment challenges the fear of job displacement, highlighting the new opportunities for human-AI collaboration in a rapidly evolving job market. The AI economy is not just about creating algorithms; it’s about the massive human effort required to train, label, and validate the data that powers them. New job titles like “data annotator,” “AI trainer,” and “prompt engineer” are emerging, creating pathways for employment for a young, tech-savvy population.

The human-centric approach is also seen in the classroom. In a bustling secondary school in Mombasa, a history teacher, Ms. Adhiambo, has embraced an AI assistant to enhance her teaching. “Before, I would spend hours grading papers and then trying to figure out where the class went wrong,” she explains. “I would have to manually mark each paper, tally the mistakes, and then try to create a lesson plan to address the common errors. It was exhausting.”

She continues, “Now, the AI gives me the answer in a minute, and I can use that time to give targeted one-on-one help to the students who need it most. It’s given me my time back and, more importantly, it’s made me a more present and effective teacher.” For Ms. Adhiambo, AI is not a threat; it’s a partner in her mission to be a more effective, and more human, educator.

Navigating the complex maze of ethics and data is a new challenge

As Kenya sprints towards an AI-enabled future, serious questions about ethics, data, and equity must be addressed. The path forward is not without its pitfalls, and a failure to navigate them carefully could have long-lasting consequences.

One of the most pressing concerns is data security and privacy, especially for minors. The use of AI in education involves collecting vast amounts of student data, from learning patterns to assessment scores. The International School of Kenya (ISK), in its AI guidelines, explicitly states that AI tools will be evaluated for compliance with Kenyan law and that students should not enter personal or sensitive data into these tools.

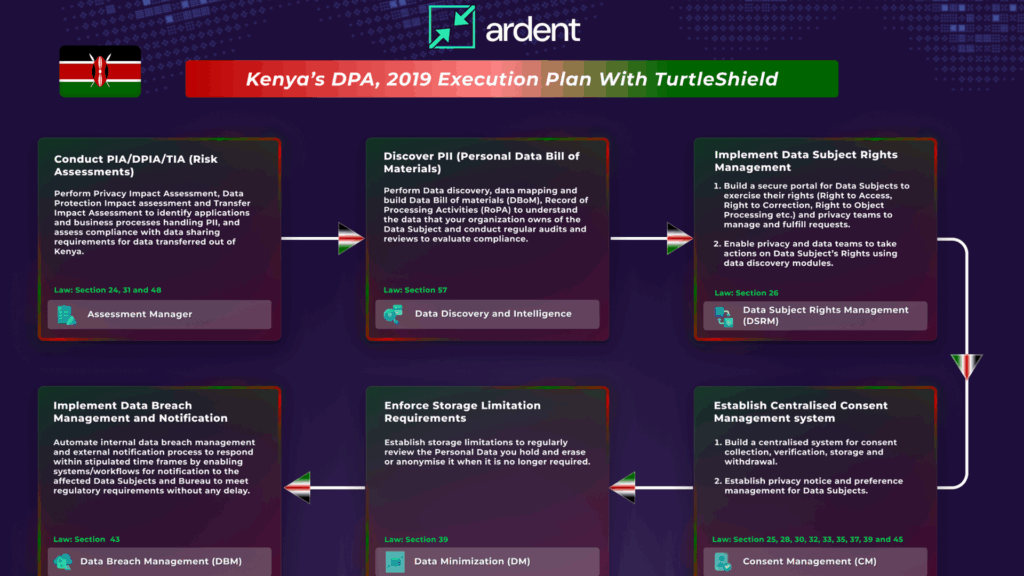

A national framework is urgently needed to protect this sensitive information and build public trust in the technology. The Kenya Data Protection Act, 2019, provides a strong foundation for this, establishing the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner (ODPC) to regulate data processing and enforce compliance. The Act requires organizations to obtain explicit consent for data collection, register with the ODPC, and report any data breaches.

Beyond privacy, there is the pressing issue of algorithmic bias. AI systems are only as good as the data they are trained on. If the data is biased—reflecting existing gender, racial, or economic inequalities—the AI will perpetuate and even amplify those biases. This is a particular concern for a country as diverse as Kenya, where historical and social disparities could be encoded into datasets, leading to unfair outcomes in areas like student placement, scholarships, or career guidance. Dr. Kitawi from Strathmore University points out that there is an urgent need to embed ethics and critical thinking into academic curricula to ensure the responsible use of AI.

The new AI strategy aims to address this by prioritizing the development of AI solutions rooted in Kenyan values and contexts, leveraging local data and talent, and incorporating indigenous knowledge. This approach, which emphasizes homegrown solutions and ethical oversight, is seen as the key to building a more just and equitable AI ecosystem.

Moving from strategy to action requires a call to arms

The story of AI in Kenyan education is still being written, and the future is not pre-ordained; it is being shaped by the decisions made today. The potential rewards are immense: a more equitable education system, a workforce ready for the digital economy, and a new generation of innovators solving African problems with African ingenuity.

To win this race, a collaborative approach is not just a good idea—it is an absolute necessity. It will require government, tech companies, NGOs, and educators to work in concert. The government must accelerate its digital infrastructure rollout, with recent announcements pledging to expand the national fibre optic network to connect 74,000 public institutions. This effort is a crucial first step in bridging the last-mile connectivity gap.

In a crucial move, the Centre for Mathematics, Science and Technology Education in Africa (Cemastea) has announced plans to train 5,300 secondary school teachers on AI and technology ahead of the 2026 rollout of the senior school curriculum. These tangible steps are the foundation upon which a truly inclusive AI future can be built.

The private sector must invest in culturally relevant, affordable AI tools and reskilling programs that meet the needs of all Kenyans. And educators must be empowered with the training and resources to become masters of these new tools, not victims of them.

Ultimately, the goal is not to replace the teacher with a machine, but to empower the teacher to be more human, more impactful, and more present for every student. The success of Kenya’s AI journey will not be measured by its ranking in a global report, but by its ability to bridge the gap between two children—one with a smartphone in Nairobi, and one with a dream in Turkana—ensuring that no one is left behind in the sprint toward a smarter, more connected future.