A mother and her children gnaw on a dry bone to survive in drought-hit Turkana. (Photo © World Vision)

By Daisy Okiring

Under the unforgiving sun of Turkana County, nine-year-old Ajuma lies on a reed mat, her limbs frail and motionless. The wind lifts the dust, but she barely flinches. Her mother, Nakiru, fans away the flies that persistently land on Ajuma’s face. “She hasn’t eaten since Sunday,” Nakiru whispers, her voice cracking. “Sometimes I chew dry maize loudly so she thinks I’m cooking. It keeps her from crying.”

Ajuma’s stomach is bloated, not from fullness, but from starvation—a tragic irony that paints the face of food poverty in Kenya. The local health center’s nurse says they’ve admitted over 40 children this month alone with acute malnutrition, and supplies are already running out.

Ajuma’s story is not unique. She is one of millions across Kenya suffering the indignity of hunger in a country that has promised “food for all” since independence.

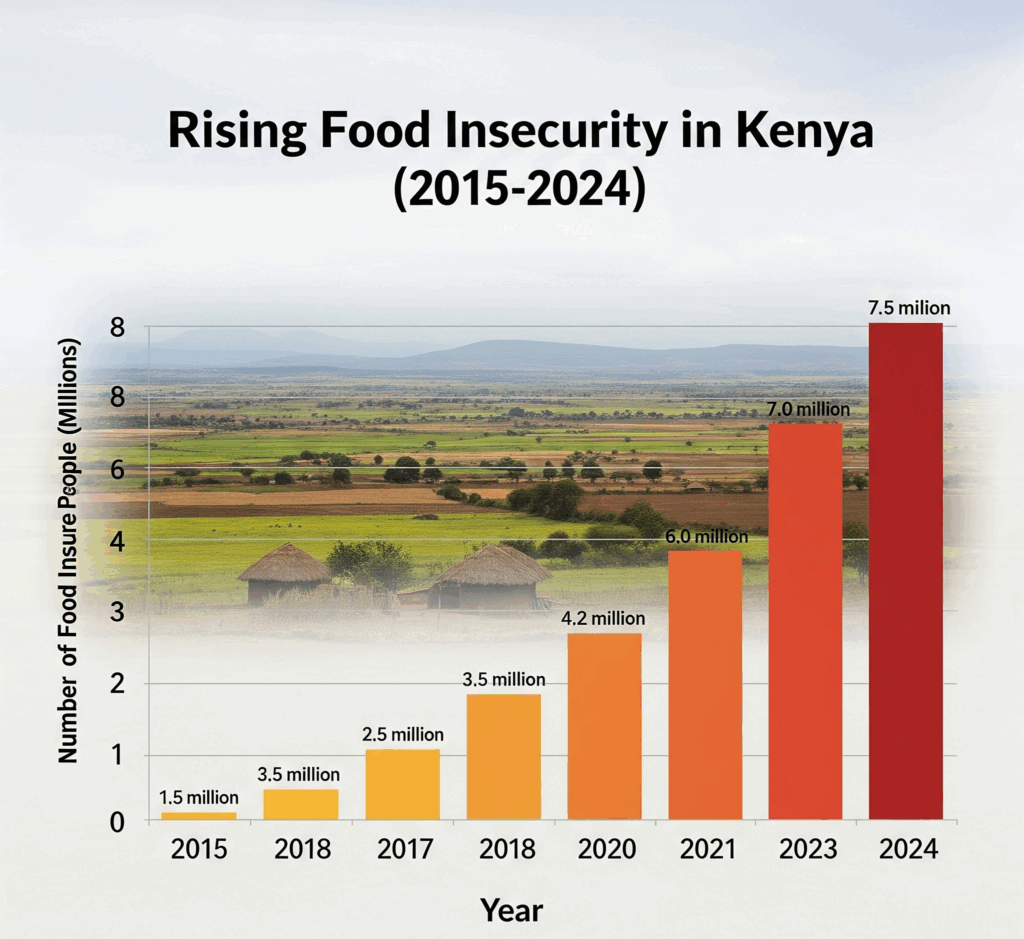

By the Numbers: A Hunger Emergency

Kenya is now gripped by one of the worst food crises in its history. According to the 2023 report by the National Drought Management Authority (NDMA), over 4.4 million Kenyans were classified as food insecure by the end of 2023. This includes not only people in traditionally arid regions like Turkana, Marsabit, and Wajir, but also urban dwellers in informal settlements such as Kibera and Mathare.

Worryingly, more than 970,000 children under the age of five are suffering from acute malnutrition, with nearly half a million in need of urgent therapeutic feeding. The crisis cuts across counties: from the pastoralist north to the agricultural heartland, climate shocks, poor harvests, and skyrocketing food prices have all collided to push millions into desperation.

The World Bank’s 2024 Economic Update on Kenya confirms that despite macroeconomic growth, the gap between the rich and the poor is widening rapidly. Food remains unaffordable for many, particularly among rural households that depend on subsistence farming or unreliable wage labor.

“This Is Not Just Drought, It’s Neglect”

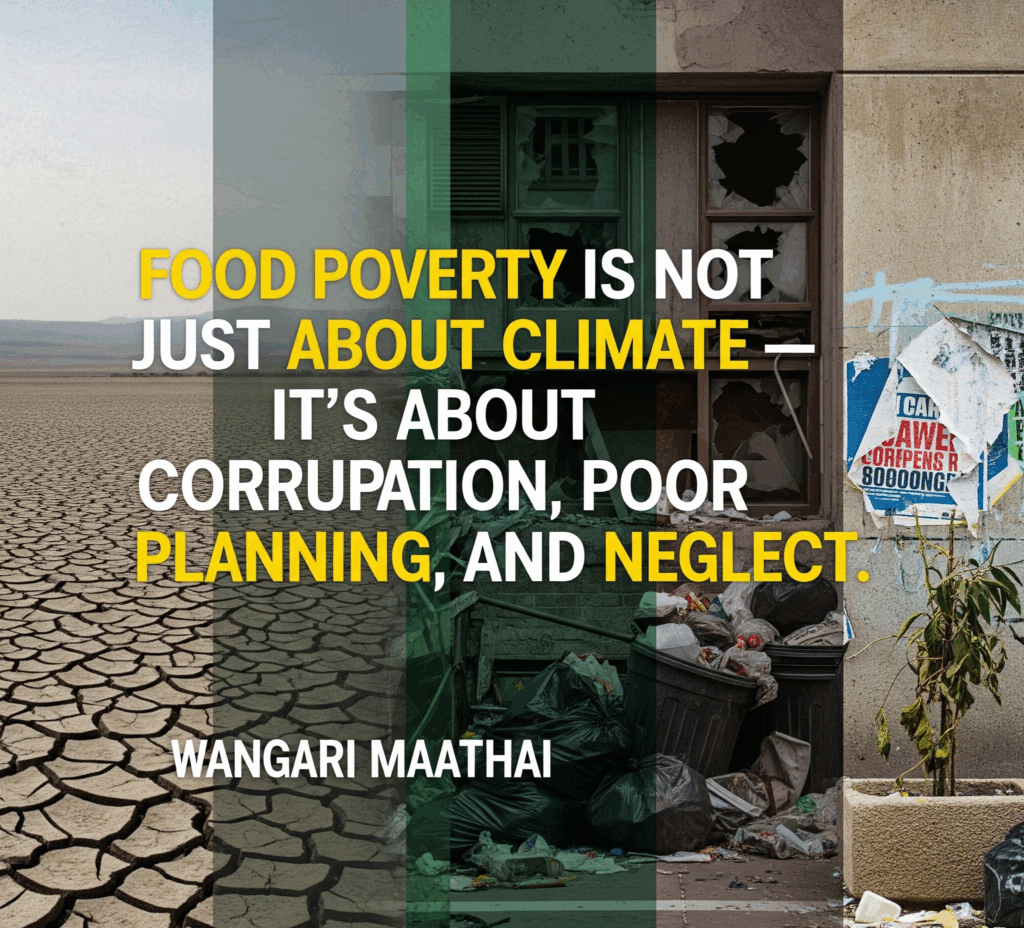

Experts argue that Kenya’s food crisis is not just a product of nature, but a result of human failure. Environmentalist Wanjira Mathai, daughter of the late Nobel Peace Laureate Wangari Maathai, emphasized this during a 2023 food security summit in Nairobi. “Climate change is the accelerant, yes. But poor governance is the spark,” she said. “We are not victims of weather alone. We are victims of broken systems.”

Read More: Illegal logging syndicates: Who’s profiting from Mau’s destruction?

Transparency International-Kenya estimates that nearly KSh 67 billion is lost annually to corruption linked to agriculture, including the mismanagement of seed subsidies, fertilizer distribution, and food relief aid. In Garissa, multiple residents interviewed reported instances where government-issued maize was intercepted and sold in local markets—often by middlemen with political connections.

It is this system of exploitation and neglect that has left people like Nakiru and her daughter in a cycle of hunger, despite the availability of food elsewhere in the country.

A Country of Plenty—For a Few

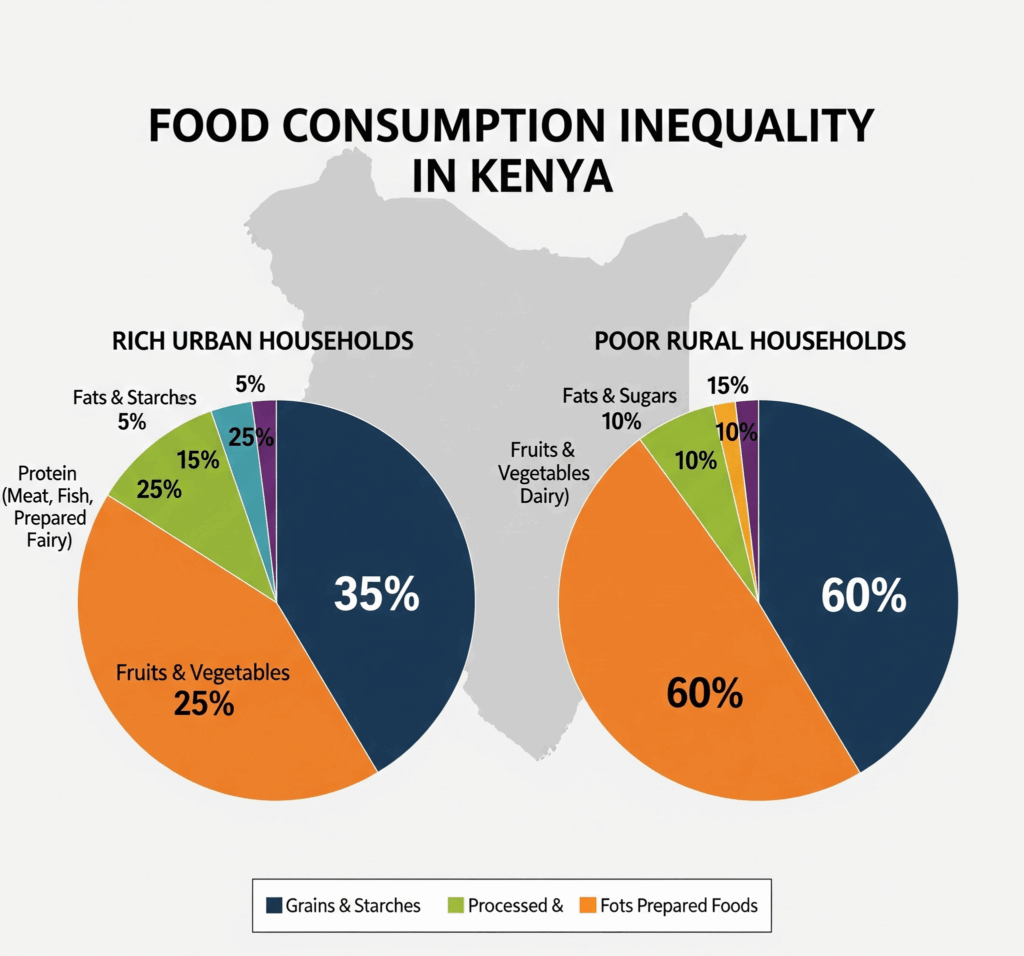

Kenya’s paradox is stark. The country produces an estimated 40 million bags of maize annually, and regions like Uasin Gishu, Trans Nzoia, and Nakuru boast some of the most productive farmland in East Africa. Yet in Mathare, a kilo of maize flour (unga) sells for KSh 170—a price most families earning less than KSh 300 a day cannot afford.

Recent data from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) reveals that the top 10% of Kenyan households consume nearly five times more calories daily than the bottom 30%. Meanwhile, reports by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) show that Nairobi’s affluent neighborhoods collectively waste more than 500 tons of food every month—enough to feed thousands of families.

Read More: Where the rain forgot us: Nomadic lives upended by drought camps

In Kibera, 60-year-old Beatrice Otieno recounts how she used to eat rice and cabbage every Sunday. “Now, even sukuma wiki is a luxury,” she says. Her meals consist mostly of porridge, with tea leaves reused up to five times before they’re discarded.

Women and Children Bear the Brunt

Food poverty in Kenya is deeply gendered. According to UNICEF’s 2024 Nutrition Report, nearly 26% of children under the age of five are stunted due to chronic undernutrition. Another 11% are underweight. These figures are higher in counties like Turkana, Mandera, and West Pokot, where maternal malnutrition and food scarcity compound the crisis.

Women, especially single mothers, face the heaviest burden. Agnes, a 32-year-old widow in Marsabit, walks eight kilometers daily to fetch water for her household of six. “I breastfeed my baby with an empty stomach,” she says. “She cries all night. What strength can I give her?”

The lack of proper nutrition has ripple effects on education. School dropout rates among girls are rising, with many families choosing to send boys to school while girls are forced to stay home to care for siblings or marry early in exchange for bride price.

Global Commitments, Local Failures

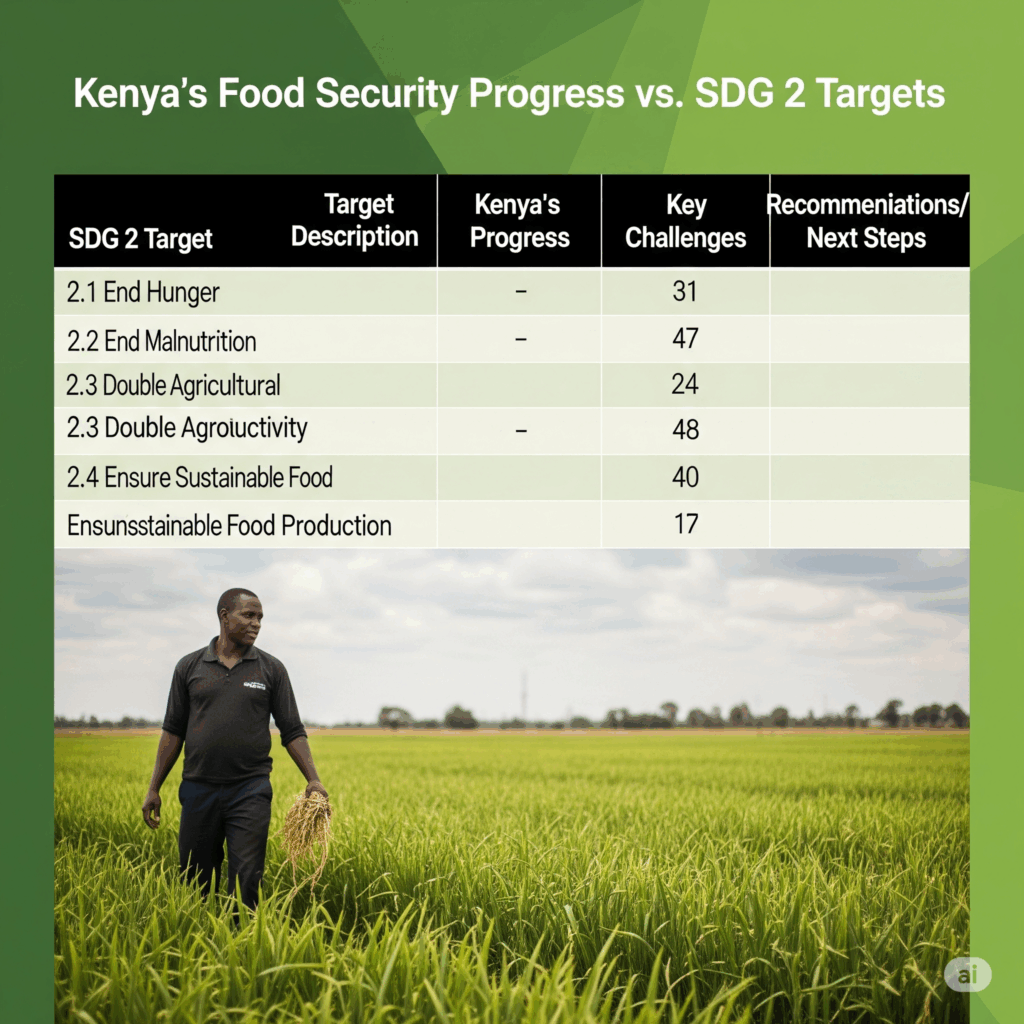

Despite signing onto the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 2—to end hunger and achieve food security by 2030—Kenya’s progress remains dismal. A 2023 review by the African Union found that 28.6% of Kenya’s population is undernourished, far higher than regional peers like Ghana and Rwanda.

In fact, Kenya has only met 39% of its food security targets under SDG 2. By comparison, Rwanda is at 61%, and Ghana leads with 74%. Critics argue that Kenya’s failure is not due to lack of resources, but poor policy execution and a lack of political will.

At the 2023 UN Food Systems Summit, President William Ruto declared, “We must end food aid dependency and produce what we eat.” But the reality on the ground tells a different story—where policy pronouncements rarely translate into effective action.

Seeds of Change—or More Broken Promises?

There are glimmers of hope, however, in grassroots and community-driven initiatives. In Kitui County, the Shamba Centre has launched a pilot project that combines drought-resistant crops with solar-powered irrigation. Local women, trained as agro-entrepreneurs, have begun reclaiming drylands to grow sorghum, millet, and cassava.

Mary Muthoni, who heads the project, says that when women are empowered to farm, they prioritize feeding their children. “When women control the farms, children eat,” she says. “But we need more support from the government.”

Read More: Lake Bogoria turns red—science says climate change, villagers say judgment day

Unfortunately, such programs are exceptions rather than the norm. Most smallholder farmers still lack access to capital, quality seeds, and guaranteed markets. Many cooperatives cite delayed payments for maize delivered to the National Cereals and Produce Board (NCPB), while promised subsidies often fail to materialize.

Organizations like Oxfam Kenya are pushing the government to allocate at least 10% of its national budget to small-scale agriculture, as recommended in the African Union’s Maputo Declaration. So far, Kenya has never met this target.

What Can Be Done Now?

Experts agree that tackling food poverty requires urgent and systemic reforms. Expanding school feeding programs, particularly in drought-affected counties, can immediately improve child nutrition and attendance. Cracking down on food aid corruption through digital tracking systems and public audits would ensure relief reaches those who need it most.

Supporting women farmers with access to land, training, and financing is critical. Investing in irrigation infrastructure can reduce dependence on unpredictable rains, and the government must consider temporary food price caps or emergency subsidies to protect poor households during inflation spikes.

Dr. Emily Mweu, a World Bank economist based in Nairobi, warns that failure to act now could embed food poverty into the country’s socioeconomic fabric. “If we continue on this path, hunger will no longer be a crisis—it will be a permanent condition for millions,” she says.

A Final Word from a Hungry Nation

In a village in Wajir County, a school bell rings to signal lunchtime. Children rush outside, bowls in hand. But only half remain. The rest, whose parents couldn’t afford the KSh 10 porridge fund, begin the long walk home with empty stomachs and heavy hearts.

These are Kenya’s forgotten children—the ones who dream of becoming doctors, teachers, and leaders, but whose futures shrink with each missed meal. For them, food is not just sustenance; it is dignity, health, and hope.

As the country marks 60 years of independence, perhaps it’s time to ask: how long can a nation claim to be free when its people are shackled by hunger?

In the words of Nelson Mandela, “Overcoming poverty is not a gesture of charity. It is an act of justice.” Until justice is served at every table, Kenya’s promise of food security will remain just that—a promise.