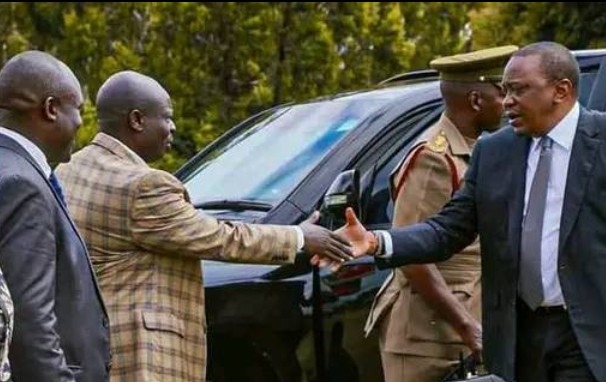

President William Ruto’s powerful aide, Farouk Kibet. Photo/TV47 Digital

By Newsflash Team

A silent but ruthless network holds sway in East Africa’s political theatre—one marked by calculation, coercion, and closeness to the pinnacle of power.

In Kenya, insiders who enjoy proximity to the presidency wield quiet but far-reaching control over even the highest-ranking officials.

Commonly known as “the system,” “the deep state,” or “the invisible government,” this covert structure is said to possess more clout than Kenya’s formal institutions. To some, its members are simply “handlers.”

Farouk Kibet: The quiet power ehind the President

Few figures exemplify this clandestine grip on statecraft like Farouk Kibet, President William Ruto’s personal assistant. Always close behind Ruto—sometimes seen as ahead of him—Farouk holds no public office and rarely gives statements. Yet insiders suggest that within the halls of State House, his voice carries more influence than many titled officials. As Ruto’s long-time aide, Farouk is widely seen as the enforcer behind the throne—controlling political machinery, brokering deals, and commanding unwavering loyalty.

His rise has been steady but under the radar. He is credited with shaping key political strategies, managing allies, and enforcing discipline within Ruto’s administration. Despite holding no formal role, Farouk’s influence since 2022 has drawn parallels with Nicholas Biwott, the infamous power broker of the KANU era. Like Biwott, Farouk thrives in the shadows but reaches into ministries, agencies, and party structures.

New public face of power

Farouk’s behind-the-scenes role has become more public. At a recent women’s empowerment event in Turbo constituency, he openly chastised Nairobi Governor Johnson Sakaja over the handling of protests. “Nairobi is our capital city; we will not allow it to go down the drain,” he declared, urging the governor to resist disruptions that affect businesses.

Those within government say no decision reaches the President without passing through Farouk. He’s seen at events issuing directives, fixing protocol errors, and coordinating the President’s schedule.

Read more: Natembeya, Farouk political war gets sour

His commanding presence has become a regular feature of public functions. Online, videos circulate of him directing Cabinet Secretaries or clearing the way for Ruto—further fueling public curiosity about his power.

Former Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua recently went on record accusing Farouk of overreach, claiming he attempted to seize control of his office. “He acts like a co-president. Cabinet Secretaries report to him,” Gachagua charged. He also named Farouk and digital strategist Dennis Itumbi as the real powerbrokers within Ruto’s administration—individuals who manage the levers of state from the President’s inner circle.

The Gatekeeper and the ‘System’

Despite the criticism, Farouk remains elusive, preferring the background to the limelight. National Assembly Majority Leader Kimani Ichung’wah once said, “You might think he’s just a simple man from the village… but at State House, if Farouk says you’re not going in, even a Cabinet Secretary can be blocked.”

Former Head of Public Service Francis Kimemia supports the belief that a deep state exists. “It’s deeper than deep,” he said. “If two candidates are neck-and-neck and the system supports one, you can be sure who will win.”

Dennis Itumbi, now a presidential insider, once battled this same deep state. He recalled being denied access to State House during the Kibaki era despite having an appointment letter. Years later, under President Uhuru Kenyatta, he wrote and released a press statement naming himself and others as part of the new Presidential Strategic Communications Unit (PSCU), bypassing bureaucratic hurdles.

Read more: Inside Farouk, Itumbi’s grip on Ruto’s political machinery

“When they tried to leave us out, I wrote the statement, had it signed, and released it before anyone could stop it,” Itumbi said. “We stayed at State House for a whole year without pay because we had technically appointed ourselves.”

Long-serving Presidential Press Service head Lee Njiru echoes the belief that true power often lies elsewhere. “The President doesn’t run the country… he pretends to,” Njiru noted. “He’s surrounded by handlers who make decisions on his behalf.”

Njiru likened the President to a farm owner detached from daily operations, while aides—“farm managers”—exercise real power. In his memoir The Presidents’ Pressman, Njiru recounted how the late President Jomo Kenyatta was neglected in old age by handlers who used his name for personal gain. He recalled instances where security personnel looted from hotels under the guise of serving the President.

“They were referred to as ‘Kenyatta’s dogs,’ but Mzee had no idea of their actions,” Njiru wrote. “They used his name to enjoy privileges and commit crimes.”

Deep State: A global reality

According to political analyst Mwangi Ayub, the concept of a deep state transcends borders. “It exists everywhere,” he said. “Governments are influenced more by unseen networks than by official structures.”

These actors may not be politicians. They could be proxies, operatives, or dealmakers—individuals who shape appointments, policies, and even security operations. Ayub cited an example from Pakistan, where unelected officials blocked a civilian prime minister from accessing nuclear data.

Read more: Ruto: Gachagua demanded Sh10 billion from me

He pointed to Kenya’s own history: Farouk under Ruto, others during Uhuru and Matiang’i’s era. “The faces change, but the structure remains.”

Extrajudicial killings, abductions, and opaque decision-making are, according to Ayub, signs of an alternative power center. “These people aren’t elected, yet they command state agents to act—and the official government distances itself.”

Building their own system

Ayub argues that each new President constructs their own version of the deep state, composed of loyalists and trusted aides. “Ruto once denied its existence. But once in office, he had to build his own power circle.”

Referring to the Rashid Echesa arms scandal, Ayub noted: “All it takes is a connection to someone close to power. That can get you appointments, protection, or tenders. It’s murky—but effective.”

He observed that these power brokers often back both sides of political divides to ensure they remain close to power, regardless of who wins. He compared Kenya’s deep state to lobbying systems in the West and likened it to characters in House of Cards—fictional perhaps, but illustrative of the real mechanics of power.

“There’s an invisible scaffolding around the presidency,” Ayub concluded. “It’s dark, informal, and deeply entrenched—yet it shapes the nation more than most realize.”