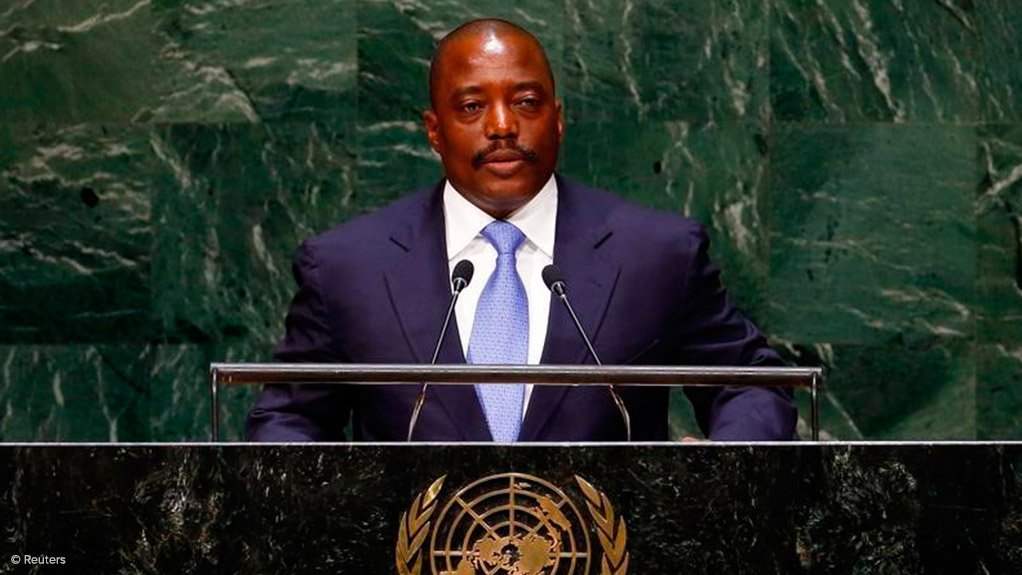

DR Congo ex-leader Joseph Kabila. Photo/X

By Daisy Okiring

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has been thrust into political turbulence after its former president Joseph Kabila was placed on trial for treason, corruption, and war crimes. The military court proceedings, which began in July 2025, have escalated tensions between President Félix Tshisekedi’s government and Kabila’s remaining loyalists.

Kabila, who ruled Africa’s second-largest country from 2001 to 2019, is being tried in absentia after fleeing into exile earlier this year. Prosecutors accuse him of secretly meeting leaders of the M23 rebel group in Goma and providing support to the insurgency, which has destabilised eastern Congo for years. The charges carry the death penalty, underscoring the high stakes of the case.

The proceedings mark a dramatic fall from grace for the man who once held near-absolute power in Kinshasa. They also raise questions about whether Tshisekedi is seeking justice—or using the trial as a political weapon ahead of next year’s presidential election.

From young warfighter to president

Joseph Kabila assumed office in January 2001 after the assassination of his father, Laurent-Désiré Kabila, who had toppled Mobutu Sese Seko just four years earlier. At only 29, Joseph was thrust into power at the height of the Second Congo War, one of the deadliest conflicts since World War II.

He had already cut his teeth as a fighter during the First Congo War of 1996–97, serving in the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo. Many of his comrades and mentors were Rwandan officers, most notably General James Kabarebe, who trained him in military strategy and politics.

During his presidency, Kabila navigated Congo through peace talks with Rwanda and Uganda, leading to a 2002 agreement that helped end regional hostilities. However, his 18 years in power were marred by allegations of corruption, persecution of political opponents, and repeated insurgencies in the east.

Despite constitutional term limits, Kabila clung to power beyond his second mandate, only stepping down in 2019 after a deal paved the way for Tshisekedi’s inauguration.

Read More: Somali intelligence confirms killing of three Al-Shabaab leaders

Exile, return, and rebellion

After leaving office, Kabila’s influence steadily eroded. By 2021, many of his allies in government and the military had been sidelined. Tensions with Tshisekedi grew as Kabila criticised the government’s handling of the M23 rebellion, accusing it of relying on poorly organised militias known as Wazalendo.

In May 2025, Kabila re-emerged in Goma, where he reportedly held talks with M23 leaders. The meeting alarmed Kinshasa, which accused him of collaborating with the insurgents. His political party, the Parti du Peuple pour la Reconstruction et la Démocratie (PPRD), was swiftly suspended. Soon after, the Senate stripped him of immunity, clearing the way for treason charges.

Government prosecutors argue that Kabila’s meeting with M23 commanders amounted to treason, given that the group has waged war against the state with alleged support from Rwanda. His assets have since been seized, and he remains in exile, believed to be moving between South Africa and other African nations.

In addition to treason, Kabila faces corruption allegations linked to billions of dollars allegedly siphoned during his presidency, as well as accountability for war crimes committed during the Congo wars.

Tshisekedi’s high-stakes gamble

The trial comes at a sensitive time for Tshisekedi, who is preparing for re-election in 2026. In June 2025, his government signed a peace agreement with Rwanda, mediated by Qatar and the United States, aimed at ending the M23 conflict.

But the deal has been politically risky. Many Congolese see Rwanda as complicit in the M23 rebellion, and Tshisekedi’s willingness to negotiate has unsettled his allies. Analysts say the Kabila trial allows Tshisekedi to divert attention from unpopular concessions and portray himself as tough on rebel collaborators.

“The court case is as much about politics as it is about justice,” said Jonathan Beloff, a researcher at King’s College London who has studied Congo’s instability. “It gives Tshisekedi a narrative of fighting traitors while deflecting criticism over the M23 peace process.”

Still, the strategy is fraught with danger. Although diminished, Kabila retains pockets of loyalists within the military and political establishment. Pushing too hard could reignite factionalism within the opposition, complicating Tshisekedi’s hold on power.

Read More: Rwanda to unveil Africa’s first self-flying electric air taxi

Implications for Congo’s fragile stability

The trial underscores the fragility of Congo’s political system and highlights how personal rivalries can influence national security. With M23 rebels still holding territory in the east, and millions displaced by ongoing violence, the focus on Kabila risks diverting attention from pressing humanitarian and security challenges.

Critics fear that prosecuting a former president for treason—especially in absentia—could set a precedent for political witch-hunts, eroding confidence in Congo’s justice system. Supporters argue it is a necessary step toward accountability in a country where leaders have often ruled with impunity.

For ordinary Congolese, the outcome may matter less than whether Tshisekedi can restore peace and deliver basic services. As the trial drags on, many worry it could deepen political divisions instead of uniting the country against common threats.

Whether Kabila ever returns to face justice remains uncertain. But for now, his name is once again at the centre of Congo’s turbulent politics—casting a long shadow over Tshisekedi’s presidency and the nation’s fragile peace.