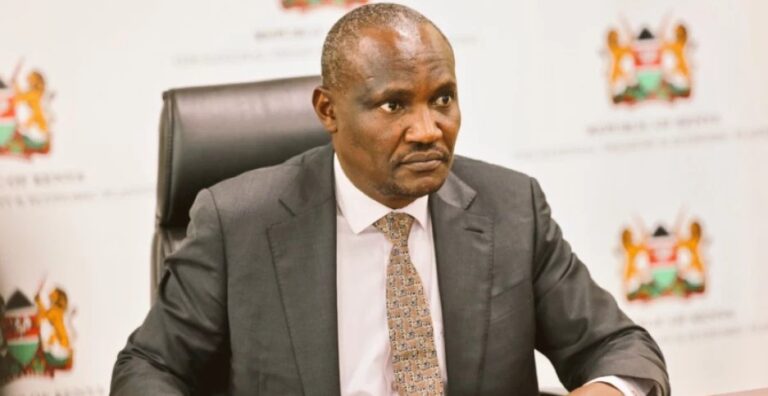

Cabinet Secretary for Energy and Petroleum, Opiyo Wandayi speaking at Orenge Secondary School in Sidho, Kisumu County on June 28, 2025.

NAIROBI, Kenya – July 23, 2025 – Kenyan motorists and households are bracing for tougher economic times as the nation’s fuel subsidy kitty has reportedly been depleted, leading to a significant surge in pump prices.

The Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Authority (EPRA) announced new maximum retail prices this week, with Super Petrol, Diesel, and Kerosene all seeing substantial increases for the period spanning July 15 to August 14, 2025.

In Nairobi, a litre of Super Petrol is now retailing at Ksh 186.31, Diesel at Ksh 171.58, and Kerosene at Ksh 156.58. These hikes represent an average increase of approximately Ksh 9 per litre across the board, pushing fuel costs to levels not seen in months and rekindling public debate on the sustainability of government intervention in the energy sector.

The drying well of subsidies

For years, the Kenyan government has intermittently used a fuel subsidy mechanism, primarily funded through the Petroleum Development Levy Fund, to cushion consumers from the volatility of global oil prices. However, the Treasury has confirmed that the funds allocated for price stabilization have been exhausted, leaving consumers exposed to the full impact of international market dynamics and domestic taxes.

Sources indicate that the previous administration under President Uhuru Kenyatta had heavily relied on the subsidy to manage the cost of living. Upon assuming office, President William Ruto largely removed these subsidies, terming them unsustainable and prone to abuse, including the creation of artificial shortages. While some targeted subsidies on diesel and kerosene were occasionally reinstated, the current situation suggests a full withdrawal of price support.

Factors driving the surge

The latest price review by EPRA attributes the increases to a rise in the average landed cost of fuel between May and June 2025. The cost of imported Super Petrol rose by 6.45 percent, diesel by 6.27 percent, and kerosene by 6.95 percent.

Energy Cabinet Secretary Opiyo Wandayi, while appearing before the National Assembly Energy Committee, defended the government’s stance, attributing the higher pump prices primarily to Kenya’s heavy taxation regime rather than inefficiencies in the government-to-government (G-to-G) oil import arrangement. He highlighted that taxes and levies account for approximately 45 percent of the current retail price of petrol in Nairobi (Ksh 82.33 out of Ksh 186.31).

Read more: Israel-Iran war threatens Kenya’s G-to-G fuel deal

“The taxes in our neighboring countries are lower – and that is in their wisdom and the wisdom of their parliaments. That’s why their fuel prices are lower,” CS Wandayi stated, pointing to the Road Maintenance Levy and the ad valorem nature of taxes, which increase as global prices rise.

This explanation, however, faced pushback from lawmakers, including Nyatike MP Tom Odege and Embakasi South MP Julius Mawathe, who challenged the notion that Parliament is directly responsible for setting fuel prices.

Ripple effect on the economy

The depletion of the fuel subsidy and the subsequent price hikes are expected to have a significant ripple effect across the Kenyan economy. Transportation costs for goods and services are set to rise, likely translating into increased consumer prices for food and other essential commodities. This will put additional pressure on households already struggling with the high cost of living and stagnant salaries.

Read more: Kenya leads Africa in digital agricultural payments

Economists warn that without effective intervention, the sustained high fuel prices could fuel inflation, hindering economic growth and potentially leading to public discontent. The government faces the delicate balancing act of managing its fiscal responsibilities and cushioning its citizens from the brunt of global economic shocks.

As Kenyans grapple with the immediate impact of the price hikes, the long-term strategy for fuel price stabilization remains a critical discussion point. The government’s commitment to avoiding fossil fuel subsidies, as communicated to institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF), suggests a sustained period of market-driven pricing. This approach, while potentially painful in the short term, is aimed at ensuring fiscal discipline and aligning the economy with a low-carbon transition in the long run.