Hero shot of cyclists riding past zebras and giraffes at Hell’s Gate. Photo/Istock

By Daisy Okiring, Naivasha, Kenya – September 7, 2025

With tourism responsible for nearly eight percent of global emissions, Kenya is testing cycling safaris at Hell’s Gate as a low-carbon alternative to diesel-fueled game drives.

On a cool Naivasha morning, the sound of crunching gravel fills the air as a group of cyclists pedal through the rugged cliffs of Hell’s Gate National Park. The usual growl of diesel safari vans is absent. Instead, zebras graze undisturbed as giraffes lift their long necks above the acacia trees, watching the cyclists glide past. The moment is serene, adventurous, and environmentally clean.

Cycling safaris, once seen as a quirky alternative for backpackers, are now emerging as a serious eco-tourism product. They are silent, affordable, and produce none of the tailpipe emissions associated with fuel-hungry Land Cruisers. More importantly, they are helping Kenya align tourism with its climate commitments at a time when the urgency of reducing carbon footprints has never been greater.

Tourism and the carbon challenge

Tourism contributes nearly 10 percent of Kenya’s gross domestic product and employs close to one million people, according to the Ministry of Tourism. Wildlife safaris remain the crown jewel of this sector, attracting nearly two million international visitors each year. Yet the industry’s reliance on carbon-intensive transport is a growing concern.

Globally, tourism is responsible for about 8 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, according to a study published in Nature Climate Change. Transport accounts for the largest share. Safari vehicles are typically modified four-wheel drives that burn up to 14 liters of fuel for every 100 kilometers, releasing around 33 kilograms of carbon dioxide in a single game drive.

Also Read: Who really benefits from Kenya’s carbon credit deals

During high season in the Maasai Mara, more than a thousand safari vehicles can operate daily. The cumulative emissions are substantial. The International Energy Agency notes that transport accounts for nearly 25 percent of all global energy-related emissions, and tourism is a major contributor.

Kenya, already vulnerable to droughts, floods, and unpredictable rainfall, is losing about 2.6 percent of GDP every year to climate change impacts, according to a 2022 World Bank report. Reducing emissions in tourism is therefore not just a global responsibility but also a national priority.

Hell’s Gate: a natural laboratory for eco-tourism

Hell’s Gate National Park is uniquely positioned to pioneer low-carbon tourism. Covering just 68 square kilometers, it is one of Kenya’s smallest parks but also among its most unusual. The park lacks large predators such as lions, which makes it safe for walking, rock climbing, and, most famously, cycling.

With dramatic cliffs, gorges, geothermal vents, and sweeping grasslands, Hell’s Gate offers a safari without fences. Visitors can cycle alongside zebras, buffalo, warthogs, and giraffes. The park’s landscape is also the inspiration behind Disney’s The Lion King.

Also Read: COP fatigue: Why Africa must lead its own climate agenda

According to Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), the park receives around 150,000 visitors annually. Many of them opt to hire bicycles at the gate or from nearby Naivasha town, paying between 500 and 1,000 shillings per day. Local youth groups and small businesses run the rentals, creating jobs and entrepreneurship opportunities.

In 2020, Hell’s Gate was declared a UNESCO Global Geopark, a recognition that highlights not only its geological significance but also its potential as a global model for sustainable tourism.

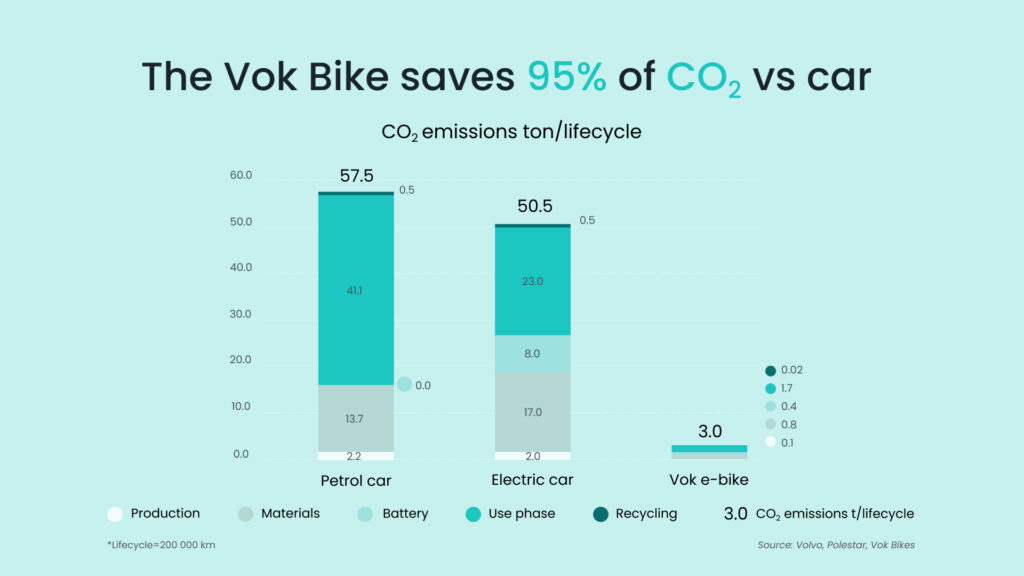

Pedal power versus petrol power

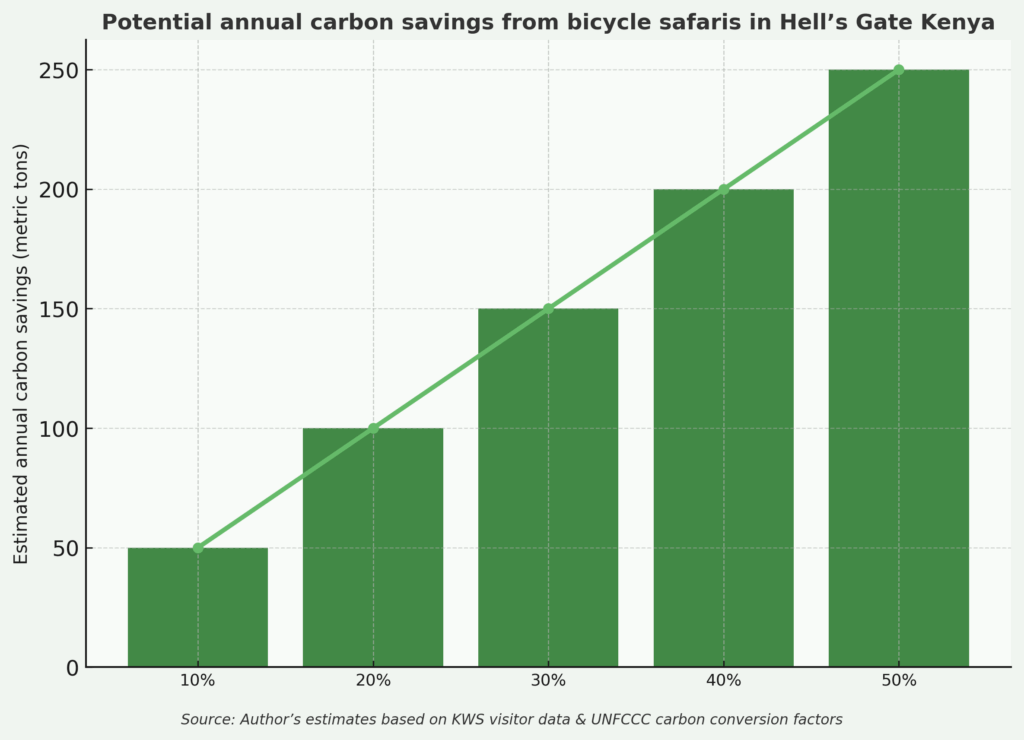

The climate benefits of cycling safaris are straightforward. A typical two-hour game drive in a diesel vehicle covers about 40 kilometers and emits more than 13 kilograms of carbon dioxide. In contrast, a bicycle safari of the same distance produces zero emissions during operation.

If even a quarter of Hell’s Gate visitors chose cycling over vehicles, it would avoid more than 400 tons of carbon emissions annually — the equivalent of planting over 18,000 trees, based on UN carbon conversion estimates.

Cycling also offers tourists a slower, more intimate experience. Riders can stop at will, listen to birdsong, and connect with the landscape in ways impossible from inside a vehicle. This aligns with a growing global shift towards experiential and sustainable travel. Booking.com’s 2023 Sustainable Travel Report found that 80 percent of travelers want to choose eco-friendly options, though many say such choices are not yet visible.

Adventure tourism, which includes cycling, is among the fastest growing segments of the industry worldwide. Allied Market Research projects it will reach $1.6 trillion by 2030. Hell’s Gate is well placed to tap into this demand.

Communities at the center of change

For local communities around Naivasha, cycling tourism is more than a climate solution. It is also a livelihood. Bicycle rentals, guiding, and small hospitality businesses provide employment for hundreds of young people.

On weekends, enterprising mechanics repair punctures and tune gears for visitors. Women’s groups sell refreshments and handmade crafts at the park’s entrances. Guesthouses in Naivasha town advertise cycling safari packages to attract eco-conscious visitors. The ripple effect extends far beyond the park gates.

Former Kenya Wildlife Service Director General John Waweru once remarked, “Cycling safaris create jobs for young people while reducing pressure on the park’s fragile ecosystem.” His words capture a key lesson from conservation history: communities thrive when tourism benefits them directly.

In Hell’s Gate, this principle is playing out in real time. Revenue from cycling safaris, though modest compared to mass-market game drives, is helping diversify livelihoods and reduce over-dependence on fragile ecosystems.

Policy, pledges, and the path to carbon neutrality

Kenya has committed to becoming a carbon-neutral tourism destination by 2050. The Climate Change Act of 2016 and the Sustainable Tourism Master Plan both emphasize eco-tourism as a pathway to meet this goal. Cycling safaris align neatly with these strategies, offering a practical way to cut emissions while diversifying the visitor experience.

In 2023, the United Nations Environment Programme’s Africa office in Nairobi highlighted cycling tourism as a “flagship model for low-carbon travel in East Africa.” The government has also supported cycling events such as the annual Hell’s Gate Bike Race, which attract international participants and showcase Kenya’s natural beauty through sustainable mobility.

Yet challenges remain. Investment in quality bicycles, well-marked trails, and safety measures is still limited. Marketing efforts often underplay cycling in favor of traditional vehicle-based safaris. To achieve scale, Kenya must invest in infrastructure and promote pedal-powered tourism as a mainstream product, not a niche add-on.

Also Read: The hunger paradox: Why africa feeds the world but can’t feed itself

Barriers on the road

Cycling safaris face both practical and perceptual barriers. Infrastructure is a key issue. Many of the bicycles available for hire are second-hand and poorly maintained, leading to safety risks. The trails, though scenic, can be rough and uneven, requiring upgrades to meet international standards.

There are also wildlife risks. While Hell’s Gate is predator-free, buffalo and baboons can pose challenges to cyclists. Park rangers advise caution, and guided rides are often recommended.

Perhaps the biggest hurdle is perception. For many tourists, especially first-time visitors to Africa, the safari image is synonymous with open-roofed jeeps crossing vast plains. Convincing them that a bicycle ride offers an equally authentic — and arguably more sustainable — experience requires strong storytelling and marketing.

Expanding the model

Despite these obstacles, momentum is building. Hotels around Lake Naivasha are increasingly packaging cycling safaris as part of broader eco-adventure itineraries. Some are exploring electric bicycles to cater to older or less fit travelers, opening the product to a wider audience.

There is also talk of expanding cycling tourism into buffer zones around Amboseli and Lake Nakuru, where controlled trails could allow pedal-powered exploration without disturbing wildlife. The potential to integrate cycling with other low-carbon activities such as hiking and kayaking could create multi-day eco-circuits that appeal to climate-conscious visitors.

Globally, cycling tourism has proven transformative in destinations like Costa Rica and Slovenia, where it has boosted rural economies while conserving landscapes. Kenya could draw lessons from these models while tailoring them to its own unique wildlife and cultural assets.

Cycling into a climate-smart future

Cycling safaris in Hell’s Gate are more than an adventurous novelty. They are a glimpse into a future where tourism reduces its carbon footprint while enriching communities. They show that conservation and development can align when innovation is embraced.

Kenya’s landscapes are already under pressure from climate change. Tourism, one of the country’s most valuable sectors, must adapt to survive. Pedal-powered safaris are a symbol of that adaptation — one where the silence of a bicycle ride through a gorge speaks louder than the roar of an engine.

As Najib Balala, Kenya’s former Cabinet Secretary for Tourism, put it: “Sustainable tourism is not an option, it is a necessity.” In Hell’s Gate, visitors are discovering that sustainability can also be exhilarating. Each turn of the wheel is not just a journey through a park but a step toward a climate-smart future for Kenya and beyond.